Do you know what your environmental footprint is? How do you feel about it? Are you doing your best to live and travel sustainably?

Or is global warming just a hoax? (Just kidding—it’s obviously not.)

In this article we’ll look at the negative effects of “digital nomading” and frequent travel—and what we can do about it. It even turns out that we can become happier in the process…

But first, I have some exciting news to share:

Nomad Gate has partnered with Trees for the Future in an effort to plant trees—both to help the environment and impoverished farmers in areas that have seen destructive deforestation.

We will plant:

- 🌲 1 tree for every new signup to Nomad Gate (it’s free to join)

- 🌲 1 tree for every new reply in the community forum

- 🌲🌲🌲 3 trees for every new topic in the community forum

We’re not only doing this for new signups and forum posts going forward, but have also counted all signups and forum activity since the launch of the Nomad Gate community!

Together, we’ve planted 118,100 trees so far 🌲🌲🌲

(updated quarterly)

Log in to see how many trees you’ve plantedJoin Nomad Gate to plant your 1st tree

Together, we’ve planted 118,100 trees so far! 🌟

(updated quarterly)

… of these trees were planted on your behalf:

This number includes the trees we will plant on your behalf in the current quarter. Write in the forum to plant more trees! 🌲

Donate directly to Trees for the Future

Before exploring why I chose to partner with Trees for the Future, let’s take a step back a look at the impact we frequent travelers have on the environment—and how we can live more sustainable lives.

Digital nomads and emissions 💨

Let’s take me as an example.

I’m a minimalist with few material possessions, usually live in small (often shared) apartments, eat a mostly vegetarian/pescatarian diet, don’t own any vehicles, and walk or take public transport almost everywhere I go. Compared to most westerners, my day-to-day environmental footprint is pretty modest.

On the other hand, my travel related footprint has been significant.

With dozens of flights each year, and at least a handful of those being long-haul, air travel alone causes over 75% of my CO2 emissions.

Perhaps as much as 15-20 metric tons (!) per year during most of the 2010’s.

I may be a bit worse than the average nomad—many of whom travel more slowly or stay on a single continent—but I don’t think my travel pattern is that unusual. And compared to those who travel a lot internationally for business, my footprint is close to negligible.

As the number of digital nomads (and other frequent travelers) continue to increase, our collective environmental impact could be quite severe.

Solutions 💡

Don’t worry—I’m a pragmatic guy. I won’t suggest we stop flying altogether and use a sailboat every time we travel to another continent. After all, travel promotes peace and prosperity through cultural understanding and trade.

In this section I’ll outline a few simple things we can all do to make up for the impact we have on the planet.

Be intentional about consumption 🛍

Most of us—especially in the developed world—suffer from what I like to call mindless consumerism.

We buy loads of useless stuff in an attempt to feel happy—or at least slightly less shitty about ourselves.

The problem is that it doesn’t work.

Things such as luxury goods, a bigger house, a fancier car, or anything purchased to project status (such as designer brands) are what Jonathan Haidt calls happiness traps in his book The Happiness Hypothesis (I recommend you read the whole book, but in particular chapter 5 talks about this). We think they will improve our happiness, but they have no positive impact over time.

The same goes for common goals such as making more money (assuming you’re not struggling to pay for life’s bare essentials such as housing, food and healthcare), thanks to the principle of the hedonic treadmill—the concept that us humans quickly adjust to both positive and negative life events and return to our “base level” of happiness.

While there are some sources of misery we never completely adapt to (meaning they negatively impact our happiness for as long as we continue experiencing them)—such as having a long daily commute in heavy traffic or being exposed to loud, intermittent noise levels—there are also some things that can increase our happiness above our base level. These include more time off from work (especially when spent doing activities with others) or dealing with things that are making you self-conscious or anxious.

So, in short: Earn less money by working less, spend less on useless stuff, spend more quality time with others. This is not only good for planet Earth—but also for your own happiness.

Here are some actionable tips to get you started in that direction:

- Cancel that Amazon Prime subscription (to increase shopping friction). You (and the planet) are better off with less frequent, slower orders.

- Don’t buy things right away. Instead, add them to a list and re-evaluate a few weeks later if it’s really something you need.

- Share apartments when practical (with your partner and/or others).

- Declutter, sell or donate stuff you don’t need, and buy fewer things going forward.

- Reduce exposure to ads and other things (e.g. social media accounts) that make you feel like you need to buy stuff to keep up.

There are many great benefits to being intentional about what we consume:

- You save money (which you can use to save for your retirement).

- You save mental bandwidth by owning less (so your things don’t end up owning you).

- You help the planet through consuming fewer resources and reducing your environmental footprint.

A note on mindful travel 🚆

In recent times there has been an increasing focus on plane travel as a dominant source of emissions, especially through what has been dubbed flight shaming.

But here’s the thing: It’s not only plane travel that’s the problem—it’s travel, period.

While ground transportation is better for shorter distances, for longer distances planes produce fewer emissions per kilometer than even most trains.

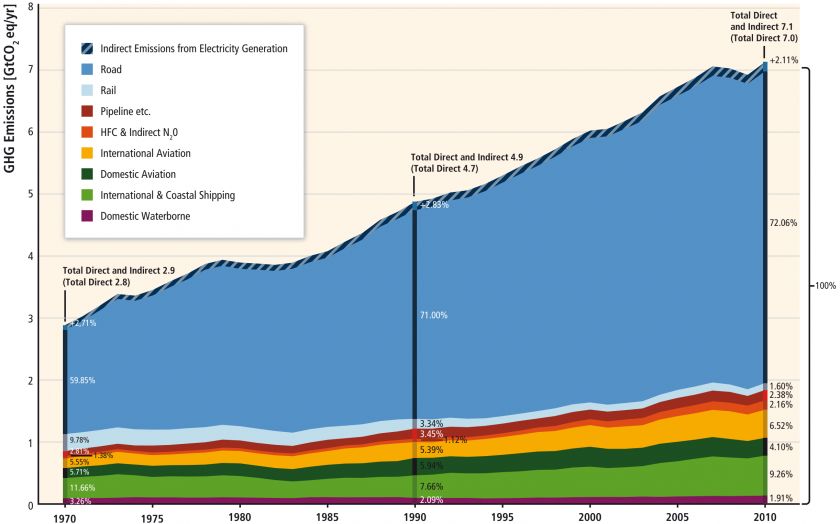

And if you look at the greenhouse gas emissions from various transportation sectors, you see that road transportation is responsible for nearly 7x the amount of emissions compared to domestic and international aviation combined:

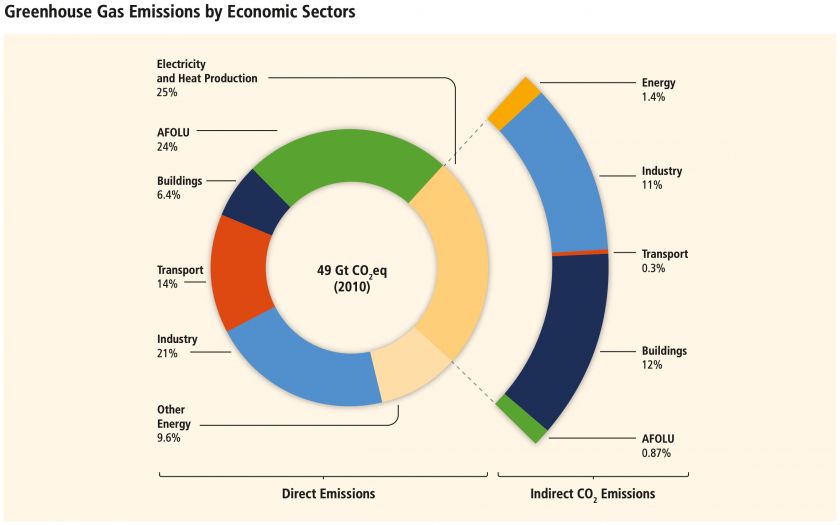

At the same time, the transportation sector is responsible for about 14% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions:

This means that aviation is responsible for about 1.5% of global GHG emissions (although this has increased somewhat since the above study was published).

In other words there’s no need to lose sleep over your annual flight to see your family over the holidays—even if they happen to live on the other side of the globe.

However, it helps if we all (especially those of us that travel a lot) are more mindful of how often and how far we actually need to travel.

Here are some ideas:

- Make fewer, extended trips by:

- Combining trips to the same region into one longer trip by careful planning.

- Spending several months in each region by working remotely (instead of making several trips over the year).

- Choose (electric) train travel where available and convenient (short to medium distances).

- Carpool or take public transport when convenient for shorter trips.

- When you fly, prefer direct flights and choose economy over the premium cabins.

- Explore destinations that are closer in proximity to where you are.

But the data also shows that even though individual behavior change is necessary, the impact each of us has is insignificant on its own. That’s why one of the most powerful things you can do to help the environment is to impact the behaviors of thousands or millions of others through influencing policies and people’s attitudes.

For example, I’d love to see Pigouvian taxes applied to all polluting industries, including all forms of transportation (road, shipping, aviation, etc).

A Pigouvian tax corrects what economists call a “negative externality”—a market failure where the cost of a good or service does not reflect the true cost to society, only the direct costs to whoever produces it. A prime example of a negative externality is pollution. By charging a tax on activities that pollute—e.g. higher taxes on fossile fuels—we change the incentives so it becomes less attractive to continue that activity.

The revenues generated from such taxes can either be used to fund environmental projects directly, or be handed back to taxpayers in the form of tax cuts elsewhere or as an “environmental dividend”.

If you’re in a position to influence policies—that’s what you should focus on. Skipping a few flights and hang drying your clothes won‘t cut it…

Carbon offsetting & capture 🌴

While most of us won’t be able to reduce our direct emissions to zero in the foreseeable future, anyone can currently make up for their emissions by offsetting them elsewhere.

But does carbon offsetting work?

It’s a question I hear surprisingly often. While it’s only part of the solution, of course it works!

Here’s how:

- By buying an “offset” you are supporting a project that are reducing emissions somewhere else. E.g. if there’s a project that will cause a reduction of 1,000,000 tons of CO2, and it costs $10,000,000 to realize the project, then each $10 you contribute to the project offsets 1 ton of your own emissions.

- Without the support from you and others like you the project wouldn’t have been realized.

One common criticism of offsets I hear is that we can’t all just buy our way out of the climate crisis by acquiring cheap offsets—emissions need to be cut across the board.

While that’s technically true—as long as we also put a price on emissions, the more demand we create for offsets (meaning price of carbon emissions rises), the more incentives companies have to innovate and the sooner clean energy sources become preferable to fossil fuels from a purely profit-maximizing perspective.

So by buying offsets you’re not only paying for emission cuts today, you’re also speeding up the transition to clean energy worldwide.

Note that besides offsetting by reducing emissions, one can also contribute to projects that capture the CO2 that’s already in the atmosphere (e.g. tree planting). More about that below.

How to buy offsets 💸

First off, buying offsets doesn’t have to be expensive. There are plenty of projects that you can support—such as upgrading polluting cookstoves in South Asia with more efficient alternatives—that still give a lot of bang for your buck.

While you may feel you should support projects closer to where you live, I think that only makes sense if it’s at a competitive price. GHG emissions are a global problem, so it makes sense to tackle the worst problems first.

If you have $100 to spend on offsets, and you could choose between cutting 3 tons or 300 tons, of course you’d choose the latter.

The price of offsets will likely increase over time—but as we discussed above that’s actually a good thing. The more expensive it gets to buy your way out of emission cuts, the more pressure on companies to reduce their own emissions (through innovation and switching to cleaner but more expensive energy sources).

Calculating your emissions 🧮

There are many calculators that will help you estimate how much emissions you are responsible for per year. I personally like this one from the UN.

If you want more accurate estimates for specific flights you are (considering) taking, check out this calculator from ICAO. Note that this calculator does not take into account the effects of “radiative forcing” which are non-CO2 related warming effects—in this case caused by aviation. There’s no clear consensus on exactly how large this effect is for aviation, but to be on the safe side I’d recommend doubling the emissions that this calculator gives you.

Choosing a project 🔎

When choosing which project to support, look for accredited programs with e.g. Gold Standard or UN certifications.

On the Gold Standard website you’ll find projects starting at $10 per ton of CO2 emissions, while on the UN website it starts as low as $0.30 per ton!

With offset prices that low ($0.30/ton) you barely have to calculate your own emissions. Just donate $100/year and you’ll have offset 5-10x what someone with 50 flights a year would have contributed!

I think it’s a good practice to offset your flights several times over. It’s what I do, and you should consider doing the same.

Offsetting through your airline 🛫

Many airlines ask if you want to offset the emissions of your flight during the booking process. I usually do this, but I don’t subtract it when I calculate my yearly offsets.

Other airlines even offer to pay for the offsets for you. One example is Scandinavian Airlines which buys offsets on behalf of all the members of their frequent flier program (which is free to join). They will even let you buy biofuel for your flight, so you can lower the climate impact even more.

Cathay Pacific will let you contribute to high-impact Gold Standard accredited programs through their website—you don’t even need to fly on Cathay to do so (just select lump sum contribution). That’s how I’ve been buying most of my offsets so far.

The one annoying thing about their offset page is that it asks you to input how much you want to pay (in Hong Kong dollars), not how much CO2 emissions you want to offset. You’ll only see that on the next page. Currently, the price is just short of HK$20 (or about US$2.5) per metric ton of CO2 emissions. The price changes over time depending on which projects are currently being supported.

Why Trees for the Future? 🌲

Let’s try to wrap this up by going back to where we started…

While I’ve been concerned with the environmental impact of my travels for a long time, it was only when Bunq launched their Green Card (which plants one tree for every €100 you spend) that I got the idea to do the same on behalf of Nomad Gate’s members.

The great thing about tree planting is that it has the power to sequester (capture) the CO2 that has already been emitted. You need less than a handful of trees to sequester a ton of carbon in the span of their growing years (typically 20-25 years). And tree planting can also be surprisingly affordable—making it a very efficient (albeit a bit slow) method of reducing current GHG levels.

A study published last year found that an aggressive worldwide reforestation program has the potential to capture as much as two thirds (205 gigatonnes) of all human-caused carbon emissions since the dawn of the industrial revolution. But the same study also warned of the urgency of doing so, as every year that passes more land dries up and is no longer suitable to grow forests.

So we better start acting now!

After deciding to go ahead with the idea, I still needed to find a reliable partner that made sure that our contributions would have the maximum impact possible.

In the end I found Trees for the Future—one of longest running organizations in the field. After years of experimentation they have found a system that seem to be optimal both for the environment and for helping the local population where it’s implemented. They call it the Forest Garden solution:

The result is loads and loads of trees planted—over 115 million so far—meaning lots of carbon removed from the atmosphere. At the same time the process revitalizes the ground, making it easier for the farmers to grow a range of fruits, nuts, and other crops—which gives them food to feed their families and stable income throughout the year from selling the surplus production.

In summary, here’s why I partnered with Trees for the Future:

- Their “Forest Garden” approach (see the above video) not only has a positive environmental impact, it also greatly improves the life of impoverished farmers and their families.

- This innovative approach also makes sure trees are properly cared for over time (the farmers have economic incentives to care for the trees).

- They run a lean operation, keeping their costs low while still being established enough so they can spend most their income where it matters—on their programs.

- They are very transparent and have earned the Platinum Seal of Transparency from GuideStar.

- A partner of other trusted companies, such as Ecosia (the search engine that plant trees when you search).

- They have been around for over 30 years, making them one of the most experienced non-profits in the field.

I also liked the fact that they publish the number of trees we’ve planted so far (updated every quarter when I send the next check). That way you can verify that I’m staying true to my word.

In addition to the trees I plant on your behalf, I think it would be very cool if we could come together as a community to plant another 10,000 this month 💪🌴❤️.

If you have a few dollars to spare for a good cause, please donate directly to Trees for the Future on our community donation page 💚.

I’ve even created a special avatar flair on the forum for everyone who donates, so let me know afterwards (click Request) and I’ll activate it on your account!

Cover photo: Xaume Olleros for Trees for the Future.

Join  now!

now!

Get free access to our community & exclusive content.

Don't worry, I won't spam you. You'll select your newsletter preference in the next step. Privacy policy.